24 Jun Girls, Growth and GAINZ! Training the Young Female Athlete

Too often when we talk about youth sports and athletic development, we give examples of boys. And an overwhelming percent of the research in youth athlete development is conducted in boys. Hello… 1972 called – on a rotary dial phone! Have you not heard about Title IX, a federal civil rights law passed as part of the Education Amendments that protects people from discrimination based on sex in education programs or activities (including sports) that receive Federal financial assistance?

Since the enactment of Title IX, there have been significant increases on nearly a yearly basis in the number of female participants in sports, which has also created professional opportunities in some sports as well (WNBA, NWSL, LPGA, etc.). During the 2018-19 school year, the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) estimated that there were approximately 3.4 million females who participated in high school sports. For perspective, Los Angeles has a population of about 4 million, Chicago about 2.7 million and Houston about 2.4 million people. And that is just the number of high school-aged females playing sports, and does not include younger girls ages 5-13 years old.

In this blog, we want to educate coaches and parents on the normal growth and maturation of the female athlete (with comparison to male counterparts- sex differences) and also provide some practical insight into training youth and teenage girls.

In previous blogs, one of us (JCE) has outlined the general process of growth and maturation and explained it in relation to perhaps the greatest male athlete of all-time, Michael Jordan, but here the focus will be on the growth and maturation of females aged 6 to 18 years with some comparison to their male peers.

Growth and Maturation: Related but separate constructs

The process of “growing up” is the major “business” of young people during the first two decades of life. “Growing up” includes growth and maturation (and cognitive and socio-cultural development). Just so we are all on the same page – we are talking about biological growth and maturation in this first section of the article. Now, these two terms – growth and maturation – are often used synonymously and although related, they are separate constructs. Let’s take a closer look here.

Growth in body size and functional athletic capacities

Growth is defined as an increase in the size of the body or its parts. This is most often seen with height and weight but it could be also be any of the parts of the body as well, like heart and lung size, etc. or muscle mass which we will talk about later with changes in body composition.

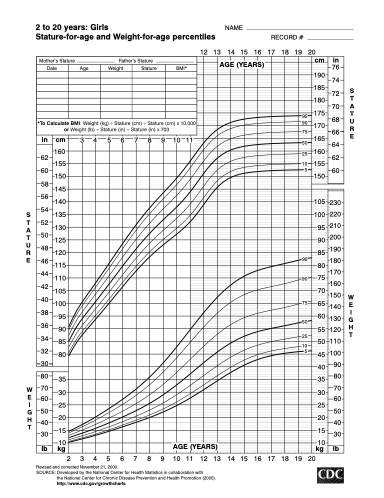

As mentioned, changes in growth are often assessed with simple measures of body size – standing height and weight. Either mom or dad ticked the wall or the nurse took the measurements during a wellness check-up. Either way, these numbers can be plotted on the growth chart.

From the growth chart, the age-specific percentile can be noted. If a girl is average height and weight, she is in the 50th percentile.

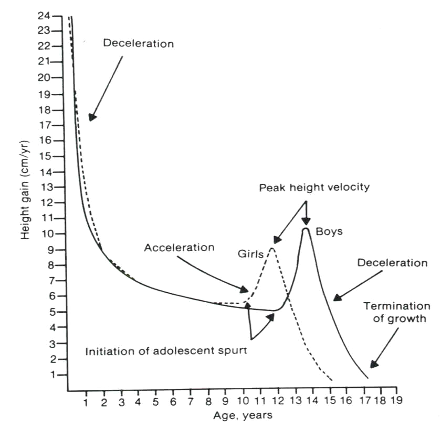

If measured and recorded periodically across childhood and adolescence, the entire growth curve can be constructed and also used to calculate growth rates (for specifics see here). The growth status on the growth chart represents the status – how far you have grown since birth, like 54 inches, etc. Like going on a car journey – we travelled 100 miles from home. The growth rate asks how fast is growth? How many inches is she growing every year? Just like our car journey we traveled 100 miles in 2 hours. The first hour we traveled 40 miles, so average speed was 40 miles per hour, and the second hour of the journey we travelled 60 miles so the average speed was 60 miles per hour. Again, we can do this for height as well – inches per year all the way along the growth journey. If we did it, the growth chart then gets converted to this graph – a velocity curve.

The stages or overall pattern of growth (in height) can be seen in both figures and are characteristized by four phases of growth across the entirety of childhood and adolescence:

1 – rapid gain in infancy and early childhood

2 – steady gain during mid-childhood (some youth will experience a mid-growth spurt between 6 and 8 years of age)

3 – rapid gain during the adolescent spurt

4 – slow increase but at decelerating pace until growth ceases with the attainment of adult stature. For girls, this may occur by age 15 or 16.

As noted in ‘Lessons in Growth and Maturation from The Last Dance’, Scottie Pippen and Dennis Rodman experienced significant gains in height post-adolescence. And, we always hear of individual cases where someone says “ya, I grew an inch or 2 in college”. However, this is generally rare with about 5-10% of the population experiencing this post-pubertal growth.

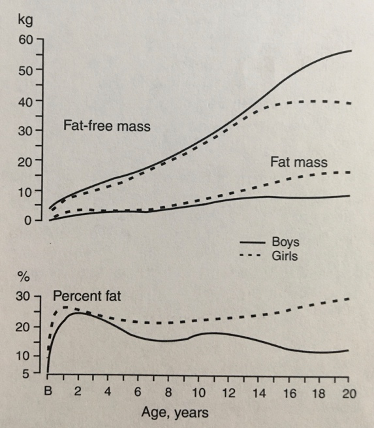

Body Composition: Muscle, Fat and Bone

The above discussion focused a lot on height. Body mass or weight and its composition into muscle, fat and bone is also an important consideration in the growing and maturing youngster, and an important factor when consider differences in athletic performance between boys and girls.

It is also a sensitive issue and sometime taboo for female athletes. Many athletic programs and sports medicine experts do not allow assessments of body weight or body composition in females as it may induce body image issues or disordered eating behavior. That is a whole other discussion.

But for now, let’s just cover the normal age-related changes in body composition of females. Please note that the data used is from a general population and not athlete or sport specific. Unfortunately, there are very few studies that have detailed the longitudinal growth and maturation of female athletes.

On average, body weight increases with age, and this is accounted for by increases in both fat mass and fat free mass (muscle and bone) until about age 14 when fat-free mass plateaus and the resulting increases in weight in females is due to fat mass. Remember, this is normal growth and maturation – girls becoming women. In essence (and without getting into human evolution), the female is physiologically preparing for reproduction, pregnancy and birth.

The percentage of body fat, which is often the number talked about in body composition assessment, is relatively stable during childhood and then begins to increase slightly during the teenage years; again this is because of the pattern of increases in fat mass with no change in fat-free mass.

Again, please note – these are average curves of females from a general population. In general, most female athletes are leaner than non-athletic peers.

Biological maturation: how a girl becomes a woman

As girls are growing, they are also maturing biologically as briefly mentioned above. In this section, we are going to focus on biological maturation – progress towards the biologically mature adult state – or how a girl becomes a woman.

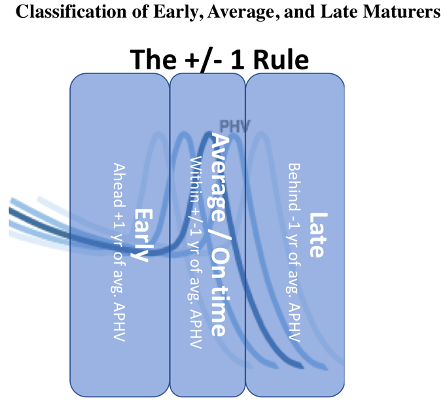

If growth is calendar time, then biological maturation relates biological time to calendar time. Or maybe you have heard people or coaches talk about biological age. You can be 12 years old (chronologically) but be an early maturer with a biological age of >13 years or a late maturer with a biological age of <11 years or on time with a biological age between 11-13 years. This can be assessed from either body dimensions or height (to be discussed below), and also more invasive clinical-type assessments such as bone age via a hand-wrist x-ray and secondary sex characteristics via assessment of what are referred to as Tanner stages of pubertal development or age at first menstruation. As you can imagine, these latter two approaches have limitations – and thus, we will focus on height.

We can use the adolescent growth spurt which was actually depicted above when showing the growth rates. But let’s dig into it a bit more to understand biological maturation and this key event of puberty.

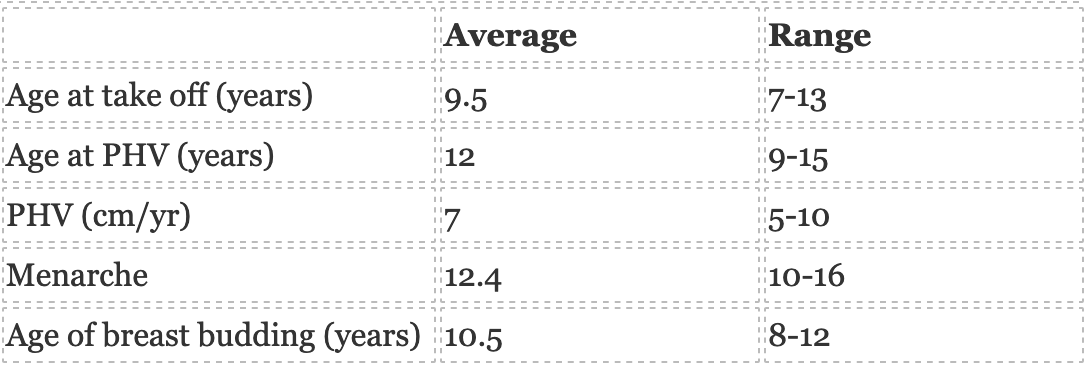

During the early elementary school years, age 6-9, there are steady gains in height of about 5cm (2 inches) per year and it will actually gradually slow until the take-off or initiation of the adolescent spurt. In girls, this occurs on average at 10 years of age (about 5th grade). As growth takes off and as Grandma says “she’s growing like a weed”, there will be a peak or maximum height gain of about 7cm (about 3 inches) in girls and this will occur on average at about age 12 (about grade 7) in girls– this is called the peak height velocity (PHV) and age of peak height velocity (age @ PHV). During this time, it can be common for girls to be a taller than boys.

A U13 soccer team.

During this time, secondary sex characteristics (a bit of a tough subject to write about in today’s society) are also developing, including breast development and structural changes in the hips and pelvis – with resultant changes in body composition as well. These changes can have a profound impact on not only the physical performance of young female athletes but also their psychology, emotions, and resulting behaviours.

These changes can have a profound impact on not only the physical performance of young female athletes but also their psychology, emotions, and resulting behaviours. Click To TweetMenarche or the first menstrual cycle or period is a central event of female puberty.

The average or median age at which girls will experience menarche is about 12.4 years of age in the U.S. And there are racial and worldwide differences. Differences have also been documented by athletic sub-groups as well with power sport athletes being earlier maturers and aestethic or ‘lean’ sports (figure skating, gymnastics, distance running) being later. (Note: a good discussion of the role of exercise training, nutrition, and stress on menstrual dysfunction and the female athlete triad is well-beyond the scope of this article. Please see this short clip by experts Drs. Mary Jane De Sousa and Nancy WIlliams)

Variability in growth & maturation

The graphs above focused on the averages. Another key point to consider about biological maturation is that it varies in the timing (maturity status at given time; when certain key events occur) and tempo (maturity progress). Yes indeed, we all know those girls who grew earlier, grew more than the average during the growth spurt, had her period earlier or later than everyone else, etc.

The table shows just how much variability or individual difference there is in the timing, tempo and magnitude of puberty for females. For example, the age at take-off into the adolescent growth spurt ranges from 7-13 years of age; the range in age at PHV can be 9-15 years old in girls; and the magnitude of the spurt or the PHV can be 5-10 cm/yr (2-4 inches).

Development of Functional Capacities in Females

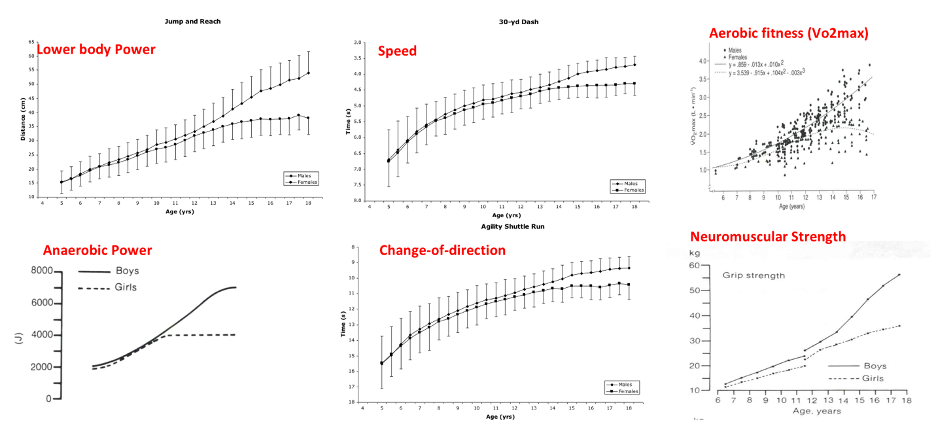

The discussion above is important to understand how girls will perform in sports, since the best predictors of physical performance during childhood and adolescence are age, size, body composition and maturity, in general.

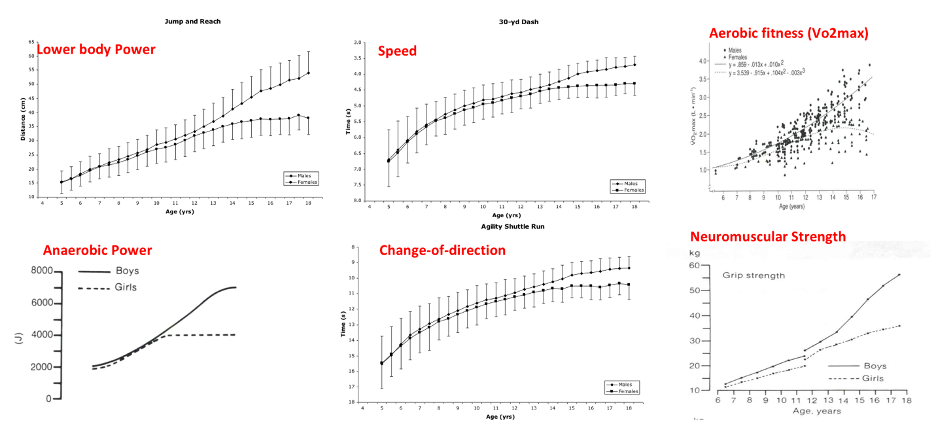

The best predictors of physical performance during childhood and adolescence are age, size, body composition and maturity, in general. Click To TweetSo how do the key measurements of physical performance or athleticism -–aerobic or cardiorespiratory fitness, anaerobic power, speed, strength, long jump and vertical jump performance, etc. – that we are so interested in testing and using to identify, evaluate and train in young female athletes How do they change with age in girls?

As you can see in the figure, and as you note during a multi-age group soccer jamboree, older girls are faster, stronger and more explosive. In general (on average), these athletic traits align quite closely with changes in body size, and more specifically with muscle mass, the “engine” that drives the performance qualities – bigger engine = faster and more powerful machine.

And compared to boys, there is very little difference before puberty. We all know girls who are faster and stronger than boys – and sometimes play in the same league – and dominate!

And then puberty starts – about 2 years sooner in girls than boys. We all remember the class photos when some or many of the girls were taller than the boys (grade 5-6).

During the latter part of puberty is also when muscle mass will generally plateau in females and this corresponds with the levelling off of functional capacities as well. Again, this is on average and most of the research data is from the general population; however, I’m sure we can also remember those girls who performed really well in middle school and maybe as freshman (especially in track and field – ‘raw’ athletic events of speed, power and stamina) and then didn’t get much better. Chalk one up for natural biology and growth & maturation, my friends.

…not another ACL injury!

Now this wouldn’t be an article on young female athletes without mentioning ACL knee injury would it?! And how often have we heard “not another ACL injury!”?

This is an immense area of research and attention in sports medicine given that the risk of ACL injury is 4-7 times greater in youth females compared to males. There are several factors involved and I am going to start the transition into training female athletes by summarizing some of the excellent work by Dr. Tim Hewitt, Dr. Greg Myer and colleagues on reducing the risk of ACL injury in female athletes.

The influence of age on the effectiveness of neuromuscular training to reduce ACL injury in female athletes (Am J Sports Med, 2014) = It may be optimal to initiate integrative NMT programs during early adolescence, before the period of altered mechanics that increase injury risk.

It may be optimal to initiate integrative NMT programs during early adolescence, before the period of altered mechanics that increase injury risk. Click To TweetDosage (how much) effects of neuromuscular training intervention to reduce ACL injuries in female athletes (Sports Med, 2014)= About 70% ACL injury was avoided if training >30 min/wk in-season (2x 15-20 min/session)

Specific exercise effects of preventive neuromuscular training intervention on ACL injury risk reduction in young females (Br J Sports Med, 2015) = strength, trunk control, plyo + strength + trunk & balance exercises increased efficacy

Compliance with neuromuscular training and ACL injury risk reduction in female athletes (J Athl Train, 2012) = Overall compliance rates <50% (range of 11% – 100%); inverse relationship between compliance and effectiveness; >66% compliance to significantly reduce risk. Take home: Ya gotta do it consistently!!

However, it is still amazing at how many coaches of female sports do not participate in a well-designed training and conditioning program that includes ACL injury prevention. Thank goodness for coaches like Erica Suter. So, I’m signing off here. Over to you Erica to focus on athletic development.

A How-to Guide to Training the Female Athlete

Thank you, Joe, for the rich introduction on growth and maturation in the female athlete – a thorough one that is yes, just glossing over the tip of the iceberg.

Yes, you heard me: we are just warming up.

I’ll admit: I feel we are writing the next Game of Thrones series with this article. What started off as a fun idea to write a casual collaboration, turned into a magical idea to write a verbose blog dissertation.

Here’s how the convo went between Joe and myself:

Joe: “We should write on growth and maturation in the young female athlete – the growth spurt, biological age, PHV, menstrual considerations, programming…”

Me: “I’m SO in.”

Joe: “I’ll be able to finish this in a few weeks.”

An hour later a message pops into my DMs on a Saturday…

Joe: “I’m already 1,658 words in…I’d estimate 2500 for my section!”

Me: *brain explodes* “I’ll get writing!”

Now here I am diving into an unending waterfall of thoughts, flowing into a stream of prose on female growth and maturation.

This is a topic I’m immensely passionate about, and could write about for eons without losing exuberance.

After being a coach for eight years in the trenches, working with thousands of pre-adolescent and adolescent female soccer players at my strength and conditioning facility, I guess you can say I’ve seen it all.

I’ve started off with girls when they were 10-year-old munchkins:

And now here I am, most of them are seniors in high school:

Oh, wait, I have several in college as well:

Truthfully, it’s been a blessing to observe the beautiful blossoming of these girls into strong women, both on and off the field.

I’ve seen girls reach their dreams to play D1. I’ve seen girls work in sport medicine. I’ve seen girls travel abroad and play soccer. I’ve seen girls go into coaching. I’ve seen girls simply become awesome human beings.

If you’re coach, growth and maturation in girls is critical to understand from a physiological, social and mental standpoint. Approaching your training and teaching with great care sets them up for empowering futures for sport and life.

Joe and I came together to write this piece to further zoom the lens in on this topic, one that hasn’t been researched enough. We wish to provide others a deep understanding of growth in young girls, from theory to research to practice.

It is our responsibility to have knowledge of female development, namely, growth and maturation, and why performance improves or declines due to uncontrollable biological factors during an athlete’s career, and how we can tweak our training to strengthen them through these times.

It’s important to know how to pivot our programming and training sessions when female athletes are in critical phases of growth and maturation, and what key components to focus on that are in our control.

Now, let me get this out of the way first: I don’t expect all coaches who work with young girls to be able to calculate Peak Height Velocity in less than 2.5 seconds without a TI83 calculator.

Nor do I expect coaches to have variability graphs on-hand and read charts with curvy lines, as they plan out the intricacies of their training sessions.

I implore you to understand the fundamentals first- to have an understanding of the big rocks of female growth and maturation, and continue to do the in-depth research for as long as young girls are in your hands.

Not only will you be smarter…

But you will program more diligently.

In youth coaching, knowledge is power, especially new knowledge

that pushes us past our old biases and ways we’ve always done things 'back in the day.' Click To Tweet

As much as coaches want to cling to the “this is how it’s always been done!” mindset, it can be dangerous.

Things like running female athletes with 30-minute Indian Runs as fitness tests, or stadium steps as punishments, as they go through rapid bone growth, programing hundreds of burpees at the onset of menarche, making them do sit-up tests for time when their spines are lengthening, or running conditioning when they’re struggling through patellar pain with no meticulously planned work-to-rest times, are doing the girls a tremendous disservice.

Looking at the wealth of science Joe provided above, there’s a lot of dynamic factors at play that impact female athlete performance – ones we must be aware of, study, learn, and take action with accordingly.

Science combined with common sense and careful practice will all be a coach’s secret weapon, and ensure his young female athletes are developing safely and effectively. Click To Tweet

Shifting gears, coaches shouldn’t be the only stakeholders in this conversation.

Parents must also be educated on what to expect during growth and maturation, and the natural processes that occur due to changes in bone growth, height, and fat mass so they aren’t frustrated when performance might wane, their kid slows, gets cut, or stagnates in a funk for a bit.

Parents must be patient and forgiving with young female athletes, and be careful before they exclaim to their adolescent girls, “you need to get faster!”

I urge coaches and parents to do this: meet female athletes where they are. Click To Tweet

As Joe alluded to above, a 12-year old girl who is an early maturer might be >13 years of age biologically, while another 12-year old who is a late maturer might be <11 years of age biologically.

Since we cannot disrupt nature, what do we do?

Focus On What You Can Control

Now that we know biological factors are out of our control, what do we focus on when it comes to training the pre-adolescent and adolescent female athlete?

There are a plethora of factors in our control, especially with ACL reduction programming. For the coaches who say, “females have wider hips,” we know. No one gets a gold star or sounds like an anatomy and physiology guru for stating the obvious anymore.

Rather, the coaches who show young girls the myriad of controllable factors in ACL reduction training, let alone, who take action on them year-round within their practices, are the ones who get a gold star.

Things we can control:

Coordination, Posture, Rhythm

Movement Patterns (squat, hip hinge, push, carry, lunge, pull)

Technique (accel, change of direction, max velocity, deceleration)

Balance (static, dynamic, loaded)

Core Stability

Mobility (thoracic spine, hip, ankle)

Conditioning (sport specific with proper work-to-rest times and volume choice)

Out of this list, the biggest issue I see in female athletes is ability to maintain a stable core.

This could be yes, disturbances in coordination, or the stupidity of programming endless sit-ups and not honing in on stabilizing the muscles of the anterior core (rectus abdominus, transverse abdominus, external and internal obliques) and low back (erector spinae) .

Here is a video tutorial that helps with stability:

Speed Development Considerations in Growing Female Athletes

Every coach and parent wants blistering speed for their young female athletes.

Speed decides the most game changing actions, from counterattacks, to one versus one scenarios, to diagonal ball bursts through the defensive gaps, to transitions from offensive to defense.

With this population, there are several speed factors to consider during pre-adolescence:

– Disturbances in coordination during Peak Height Velocity can cause speed to decline

– Increased fat mass during Peak Weight Velocity can hinder speed

– Speed takes long-term athletic development due to motor learning and training the nervous system maximal sprinting

Speed might slow down, so expect this. Of course, this does not go for all, but across the board, it goes for most young female athletes.

Here are examples of my athletes’ speed improvements over time, due to training and growth and maturation:

Athlete 1

10-Yard Sprint: 1.85 (2019); 1.81 (2020)

20-Yard Sprint: 3.48 (2019); 3.12 (2020)

Athlete 2:

10-Yard Sprint: 1.82 (2019); 1.80 (2020)

20-Yard Sprint: 3.39 (2019); 3.10 (2020)

Athlete 3:

10-Yard Sprint: 1.92 (2019); 1.81 (2020)

20-Yard Sprint: 3.32 (2019); 3.12 (2020)

Practical (Controllable) Training Solutions for Speed

Sprint more (are female athletes exposed enough to speed work? competitive? racing?)

Important reminder: speed training is not conditioning. Half the battle when getting young female athletes fast is prescribing the proper work-to-rest times when running sprint drills. Ideally, no longer than 5-6 seconds, max effort, with a 90 second to three minute rest between sets.

Half the battle when getting young female athletes fast is

prescribing the proper work-to-rest times when running sprint drills. Click To Tweet

Also, being meticulous and diligent when coaching them technique helps them to save load on the knee joint, as well as improve horizontal and vertical force production:

Reinforce use of arms ←- neural pattern must be done consistently to stick

Plyometrics

Quality is better than quantity. For all ages, plyometrics are about optimizing the stretch shortening cycle from concentric to eccentric muscle action in order to recruit fast twitch muscle fibers.

If this is too much exercise science jargon, this means improving the mystical, magical “explosiveness” every parent wishes for their child. Long duration, HIIT circuit style plyometrics are not tapping into the ATP-CP energy system for rate of force development. I wrote an extensive article Coaching Female Athletes Plyometrics: Stop Making Them Sore for an in depth explanation and some drills to do.

Here are some general rules of thumb for jumping and landing progressions for female athletes:

Here is a progression one of my 12-year-old girls did to learn the mechanics over a 4-week block:

Here is another progression as girls go from pre-adolescence to adolescence an enter into the measurable performance phase:

It’s worth taking note that when a young female athlete starts a strength and conditioning program, jumping power will improve based on training and growth. The young athlete above began with a 5’4″ broad in middle school, and now as an underclassman in high school is at a 6’9″ after two years of consistent training.

And then the ultimate progression I like to use for girls 16 and up are explosive jumps, namely, the 3x broad jump assessment when concentric to eccentric muscle actions can be trained to be more rapid:

Gradual progression that is supervised is key for this population. With so many dynamic changes occurring in the body, there is no rush to get past the good old-fashioned basics.

Remember, too, that plyometrics are not conditioning. Low volume with quality form and long rest times make female athletes explosive and powerful. Click To Tweet

Soft Skills aka ‘Anti-Abusive Coaching and Being A Kind Person to Young Girls’

Let me say this: I’ve been around the block and have seen horrific things being said to young girls.

From “F this” to “F that” to “you suck” to “you F’ed up!” and the list of abuse goes on and on and on.

Put bluntly, this needs to stop. Now.

There are a lot of charlatans out there who are vocal on Twitter and who splash across social media, ‘building strong girls!’ yet they fail to walk the walk in real life.

They yell profanity.

They treat female colleagues with disrespect.

They don’t support women in high level positions.

They berate young girls for mistakes.

Simply put, they’re not living, breathing examples of what they’re preaching.

So if you're a coach who preaches strong girls, get really clear on how you're acting. Click To TweetI dive in on this in an article I wrote Building Strong Women Starts With You, Coach. Enjoy.

This bears repeating: anyone can yell at a female athlete and run them into the ground, but not everyone can truly develop the total human and build the next generation of strong women.

Be the latter.

Be the light.

Female athletes won’t look back fondly on a coach who normalized narcissistic, abusive behavior, and who focused on wins and trophies and dropping F bombs.

No.

Female athletes will reflect back on the memories

of a coach who encouraged, supported and birthed their strengths. Click To Tweet

Female athletes will reflect on transformational leadership that was life changing.

Female athletes will reflect on the mindset skills they learned from their coach.

Female athletes will reflect on the healthy nutritional habits a coached instilled in them.

They will reflect back on a coach who had knowledge about the key components of growth and maturation, and who designed their physical training programs with great care to set them up for success for the long-run.

They will always remember the coach who cared for the human.

GET THE STRONG FEMALE ATHLETE BOOK, A SCIENCE-BASED APPROACH TO REDUCE INJURY, IMPROVE PERFORMANCE AND INCREASE CONFIDENCE IN FEMALE ATHLETES HERE

Foreword by Joe Eisenmann, PhD

Author, Erica Suter, MS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Erica Suter is a certified strength and conditioning coach in Baltimore, Maryland, as well as online for thousands of youth soccer players. She works with kids starting at the elementary level and going all the way up to the college level. She believes in long-term athletic development and the gradual progression of physical training for safe and effective results. She helps youth master the basic skills of balance, coordination, and stability, and ensures they blossom into powerful, fast and strong athlete when they’re older. She has written two books on youth strength and conditioning, Total Youth Soccer Fitness, and Total Youth Soccer Fitness 365, a year-round program for young soccer players to develop their speed, strength and conditioning.

Follow Erica on Twitter and Instagram and book a discovery call to become an online client HERE.

Joe Eisenmann, PhD, has dedicated his entire career to the development of young people in the context of physical activity, youth sports and fitness. He has 25+ years of experience as a diverse scholar-practitioner as a professor, researcher, sport scientist, coach educator, strength & conditioning coach, and youth sports coach. He is recognized as a leader in youth fitness and youth athletic development publishing 200+ scientific papers and serving on several national and international advisory committees, including acting as the chair of the National Strength & Conditioning Long-term Athletic Development special interest group. In the past few years, he has dedicated his career to knowledge translation, dissemination and implementation of best practices in youth athlete development. Currently, he is the Head of Sport Science at Volt Athletics and is also a visiting professor at Leeds Beckett University and the University of Saskatchewan.

Follow Dr. E on Twitter and explore more of his work at IronManPerformance.org

FEMALE ATHLETE BOOK RECOMMENDATIONS

She the Confident – Shay Haddow

The Young Female Athlete – Cynthia J. Stein, Kathryn E. Ackerman, Andrea Stracciolini

No Comments